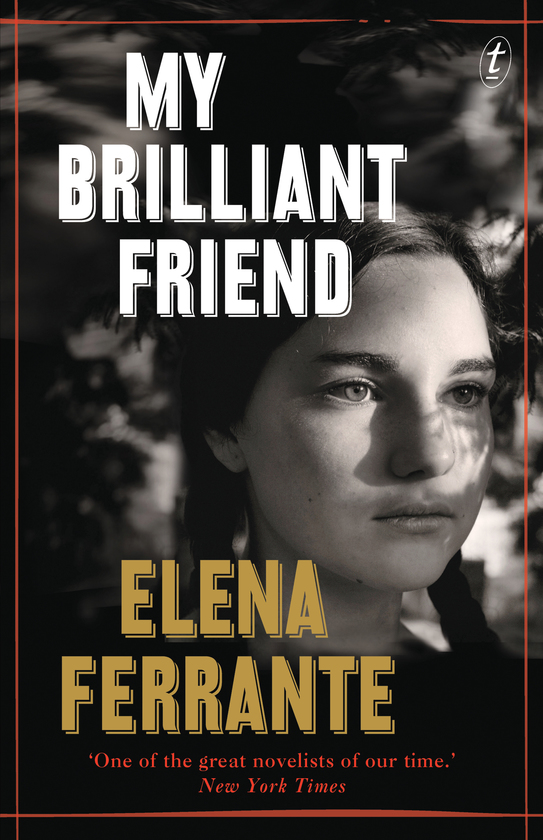

My Brilliant Friend - Author - Elena Ferrante

2015 Edition published by the Text Publishing Company (Melbourne)

ISBN 9781925240009 (paperback) $29.99 Dymocks

Best of the Blurbs: None.

The first three pages of this book contain 19 separate blurbs; each one of them, over-the-top adulation. Assaulted by this crap, my immediate response was to put the book down and not buy it. Then, I paused, "Wait, it has sold very well, and doesn't the feminine side of my psyche need renovation?" Ancient, white-hair, male, conservative, and an Anglo/Irish white Australian. "OMG, Yes!", I hear the consensus say.

An index of characters is provided , and very helpful it proves to be, in keeping track of family and Christian names. No non-traditional given names here. The families and characters of the book live in an impoverished part of Catholic Naples, circa 1960s. We are led through the tale by the first person voice of Elena, one of the two main characters. The other is her brilliant friend, Lina or Lila Cerullo. The book covers the first two stages of their lives, childhood and adolescence.

Elena is studious, kind and thoughtful - Lila, clever, cruel and impetuous. Not only is Lila street-smart, she is also school-smart. We share the pair's up and down relationship in childhood and adolescence. It's a competitive relationship in which Lila mostly triumphs. Poverty, ignorance, violence and horrid parents are constant themes. Sex, of course is also there, but in a muted tone, in keeping with the early 1960s. The kids of Naples were like me, aware of it but confused. The postmodern bonfire of profanity and promiscuity wasn't ignited until later. In adolescence, Elena's brilliant friend drops out of the scholastic side of their competitive relationship and her future is seemingly corralled by marriage and her "pleb" status. By contrast, Elena excels scholastically and is determined to change her "pleb" status. Who, now, is the brilliant friend? Although the book ends with this question unanswered, the story does not end there. This book is the first of four in the "Neapolitan Series". I look forward to reading the second book, The Story of a New Name. Presumably, Elena retains her friendship with Lila as she makes the transition from "pleb" status to middle class.

Elena Ferrante is a pen name and the main character in the book is called Elena. So is the book autobiographical or fiction? It's sold as fiction. The author claims it's fiction. My view is: it is clearly biographical, yet the first person voice of Elena is so intimate and consistent, you assume her presence. Entranced by the voice of Elena you are sucked into the illusion of reality.

The illusion is shattered, fortunately, only for a moment, by the intrusion of pedagogy. Lila coaching Lena in translating Latin: "Read the whole sentence in Latin first, then see where the verb is. According to the person of the verb you can tell what the subject is. Once you have the subject you look for the complements : the object of the verb is transitive, or if not other complements. Try it like that." So, the author is or was a teacher and like her kind, always trying to uncork the genie from the bottle of childhood. Could be the professional identity of the author is that of a teacher

Dialectic language is more likely to be used by Mary Norris, a mature-aged, self confessed "Comma Queen" and the author of Between You & Me.

Between You & Me ........ Confessions Of A Comma Queen - Author: Mary Norris

2015 Edition published by the Text Publishing Company (Melbourne)

ISBN 9781922182937 (hardback) $29.99 (Avid Reader West End Brisbane)

Best of the Blurbs: Ben Yagoda: "A delightful mix of autobiography, New Yorker lore, and good language

sense." ( Note the careful use of punctuation. I sense Mary reading over his shoulder, with a corrective eye and an unholstered pencil.). And why does this guy's name remind me of Star Wars?

"Synecdoche: what was that?" (As soon as I finished typing this word, my spell-checker asked me the same question.) "The context defined it for me-----a small thing writ large but I looked it up anyway. It's from ---the Greek syn(with)+ekdoche (sense, interpretation), from ekdechesthai "to receive jointly" : "a figure of by which a part is put for the whole (as fifty sail for fifty ships), the whole for a part (as society for high society), the species for the genus (as cutthroat for assassin), the genus for the species (as a creature for a man), or the name of the material for the thing made (as boards for stage)". It has four syllables, with the accent on second syllable: "sin-NECK-duh-kee." A near rhyme with Schenectady".

This was Mary's Road to Damascus moment. No more foot checking at the local swimming pool or driving milk trucks. On discovering this word in The New Yorker, Mary moved to New York, eventually

obtaining a job at The New Yorker, the beginning of her 30+ years career as a proof reader.

and copy editor.

Her love of words inspires her to take the reader on several, other etymological journeys. Her guide is the Merriam -Webster dictionary, anointed by The New Yorker as its supreme book of reference. Mary rewards Merriam -Webster with a potted history of its development and a neat biography of its author, Noah Webster.

The rest of Mary's book can be described as a raft of English-usage in a river of anecdotes. Mary entertainingly covers the usage of commas, hyphens, dashes, colons, semi-colons and apostrophes. An interesting aside is Charles Dickens' use of commas, punctuation by ear. Dickens' books were read in public by him and others, including actors, to entertain audiences who were unable or unwilling to read themselves, like television audiences of today. Dickens' profuse use of commas was "intended to give a lift to the voice, a pause as the [reader] .....injects a bit of suspense". By contrast, I recall reading Angela's Ashes, the childhood memoir of Frank McCourt and being swept along in its telling, unconscious of his minimalist use of commas until well into the book. Some of his sentences I discovered, were large paragraphs, with only one punctuation mark - at the end.

Mary has some pet hates and writes: "It's an inarguable tenet of punctuation : the period at the end of the sentence makes you stop and tells you that a new sentence is about to begin. Otherwise you have the despicable "run-on sentence". And yet sometimes in fiction of a very high order you see sentences that have been spliced together with commas and you wonder...Chances are that if the piece has been published, the commas are not a mistake: someone, probably the author, insisted. The express-style sentences may be telling you something about the narrator. The Italian writer Elena Ferrante (a pen name) rushes from one sentence to the next, with a breathless pause, and the cumulative effects of great urgency in the storytelling". Oops, I didn't notice this, reading, My Brilliant Friend. On checking Mary's comments, there are commas and short sentences in abundance, even when you take into account the quoted dialogue. Good punctuation is like a referee in a football match, if you don't notice him, he is umpiring well. I notice the commas in Dickens' novels; they irritate me together with the verbosity and sentimentality of the books. Thus I have read very little Dickens and felt guilty about rejecting the famous author. I have forgiven myself, now, in the knowledge that his books were written to be read aloud in public, and that he was paid for the numbers of words he wrote.

By the time Mary got around to intransitive verbs, I was done with grammar. I was in need of a refreshing anecdote, like the one investigating the origin of the hyphen in Moby-Dick. Yet, the best of the book has nothing to do with commas or hyphens. "Ballad of a Pencil Junkie", the title of the last chapter of Mary's book is a funny, informative account of Mary's obsession with pencils and erasers, essential tools of her trade. We are introduced to the world of graphite pencils including the history of their development, how they are made, Mary's preferences: a Palomino Blackwing or a Palomino Blackwing 602 - "Half the Pressure, Twice the Speed." Unlike the rest of us, Mary can boast of going to a pencil party in New York. Then she tops this, with a visit to the Paul A. Johnson Pencil Sharpener Museum in Logan, Ohio, where 3,441 pencil sharpeners are housed - each unique - no duplicates. Inside the Museum, Mary discovers it does not have a black KUM long-point sharpener. She had been given one at the pencil party. The visit ends with Mary donating it to the museum's collection, a truly generous act of philanthropy. And where else, other than in America could this happen?

The title of the book announces Mary's main complaint, the use of "You & I" instead of "You & Me". Mary's complaint is that people using You & I are snobs and worst than that, ignorant snobs. Phew!

No comments:

Post a Comment